On January 29th 1982 I was in Tiruvannamalai in Tamil Nadu in Southern India. Tiruvannamalai is a small town with a huge temple. The backdrop to the town is the Arunachala hill, which is seen as Shiva himself and is the real object of devotion here. The hill has been the abode of ascetics down the ages: in the first half of the twentieth century Ramana Maharshi lived here, and although not a guru many Indians and Westerners have devoted themselves to his teaching.

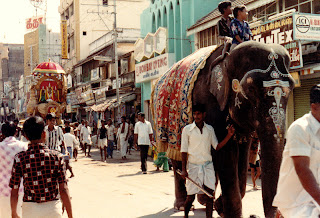

The previous evening I had gone to the temple and been impressed by its size, courtyard within courtyard, two tanks, lots of commercialism, monkeys, an elephant, even cows inside, lots of sadhus and babas, more Shiva here than I'd seen elsewhere. A brahmin hustled me down to a lingam shrine beneath a pillared hall where Maharshi is supposed to have done tapas; it has a plaque and two photos; he did a puja for me so I had a mark on my forehead which got much looked at. Many of the visitors were sitting facing the mountain.

|

| Arunachala from the temple: My picture |

In the afternoon I tackled Arunachala itself, not getting especially far up - it was too late in the day. I passed the cave where Maharshi spent many years but what I wanted was some feel of the mountain itself. I wrote this in my notebook:

I am perched on a huge boulder on the first ridge of this most holy mountain. Late afternoon, sunshine alternating with cloud shade, and there's a lot of haze. So far the climb has been dry and dusty, small herby plants, short grass and some cactus, some kites coming close to my head, a neophron landing on a rock, a pack of well-behaved monkeys, a big old male moving behind his family, slow but dignified. Above it gets a little greener, long grass and some flowers, scarcely attractive though, a small group of people collecting something, grass perhaps.Below the town is laid out. I can see almost all of it, roads leading out at strategic angles, I can see seven at least, the eternal bleating of horns, the train line on the far side, and a train chugs slowly across and stops at the station. The flat plain stretches out until it gets lost in the haze, some clumps of hills in the distance, but nothing as spectacular as this hill.The temple dominates everything; it covers almost 10% of the town area. I can make out three courtyards and the shrine within, 4 gopurams for the two outside courtyards and one for the inside one, plus two tanks, one shining green, and various porticoes and the large covered hall of pillars. There are trees in the outer courtyard on the far side. On three sides around is the town, but on this side only a few red-tiled houses before the slope of the hill. On the left is the smaller hill with temple on top and at its foot, it acts as Nandi to Arunachala itself which is Shiva. Beyond is a temple and tank, an ugly yellow school, the mosque: I heard them calling prayer-time not long ago, and I heard also the call for Friday prayers at noon.

The temple: My picture I can see one or two shrines on the slope of the hill, one with the friendly well-spoken baba, but the cave and the ashram are hidden by a fold in the hill. I cannot deny Raman Maharshi's presence; although it is the name on everyone's lips, the presence is getting rather dim, dimmed by the passing years. But the mountain lives on, that is the presence, for here the mountain is Shiva, the mountain is God, and I can sense the reverence folk have had for this extraordinary mountain over the millennia.

On the way down I stopped by the shrine with the English-speaking baba, a happy soul. "England is in London?" He came from Tirutani, near Tirupati, and had been staying at the shrine two months. He put ash on my forehead. He told me the shrine was to "Annam that is Mata, Devi," I think that is what he said.

Roger Housden in "Travels Through Sacred India" describes the walk round the mountain. The internet has a vast amount of information about Ramana Maharshi, for instance this website and this website; there is also David Godman's blog with this post of old photographs. There is also a webcam of Arunachala.